On July 18, 1994, a bomb was detonated from a van parked outside the headquarters of the Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina (AMIA) in Buenos Aires, destroying the building and killing 85 people. After a prolonged, and irregular investigation, prosecutors eventually accused the Iranian government of orchestrating the attack. Since that time, the Argentine government has been calling for the extradition of senior Iranian officials it claims were responsible to stand trial in Argentina. However, beginning in early 2012, reports began surfacing that Buenos Aires and Tehran were in talks regarding the bombing, eventually culminating in the announcement of a memorandum to begin a new, joint investigation into the attack. The memorandum signed by the two countries, though controversial, is set to be approved by the Argentine Congress. The motives behind the about-face are opaque as Iran is unpopular in Argentine with Pew Global Indicators finding in 2008 that only 10% of Argentines had a positive view of Iran’s government compared to 52% who had a negative view. While it’s possible these attitudes have changed, Iran has likely not made up a 42% game in 4 years, so why is the Argentine government making such a concerted effort to get closer to Tehran?

In general, I fail to see a tangible benefit for Argentina from such a move. Regarding the AMIA case, the quality of the initial investigation seems to have been, at best, substandard, but it seems extremely unlikely that an investigation conducted in conjunction with the accused party will be any better. So arguments that this makes justice more likely (both regarding actually trying the guilty and doing so in a way that is viewed as legitimate by Argentines in general) seem either deeply cynical or hopelessly naïve.

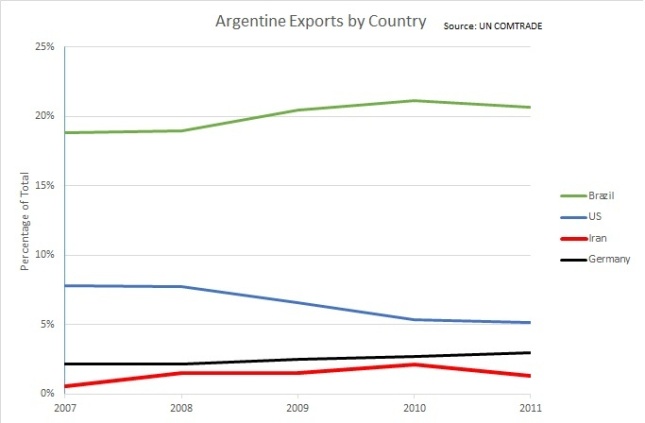

Similarly, an increasingly important economic relationship could have led to a moment of realpolitik by Argentina; deciding that potentially allowing the guilty parties to point the finger at someone else was worth the economic benefits. The problem is, Iran is not a major trading partner for Argentina, even after a surge in exports in the last half-decade. Even during that time, exports to Iran have never been more than 2.13 percent of total exports. That certainly isn’t nothing, but that still represents less than its exports to Germany and a third less than those to the United States, both countries that are in the process of applying economic sanctions against Iran. However much trade with Iran is growing, the geography and the sheer sizes of the US and EU economies relative to Iran would dictate that it’s not a relationship worth fighting too hard for.

In the end, I think that the main purpose of any move to achieve closer ties with Iran has to do with symbolism. Specifically, the symbolism of standing up to the United States. Cristina Kirchner has long expressed her desire for a more multipolar world and is a product of the ardently anti-American leftist wing of the Juventud Peronista in the 1970s, so in that sense, it’s hardly surprising. Iran essentially represents the epitome of resisting the United States but it also has virtually nothing to offer to oil producing countries that support it (Venezuela, Ecuador and, to a lesser degree, Argentina) and everything to gain from the diplomatic cover the provide it. However, symbolism can only go so far, and Iran’s conservative theocracy has little in common with countries like Argentina, which have a decidedly secularist and Marxist flair to them. From a more pragmatic position, bandwagoning with a rising power like China has way more to offer a country like Argentina if it is looking to be more in opposition to the West. However, China’s self-interest leads it to pragmatically associating with countries outside its neighborhood based on their economic value (and, in some places their position on Taiwan) and is less easily courted. It also is only indirectly in opposition to the US and therefore lacks the powerful symbolic value that siding with Iran offers.

Basically, Cristina Kirchner has calculated that the benefits of playing up her anti-American credentials to her base will outweigh the negative domestic effects regarding the AMIA case while any rebuke by the US will draw to the surface the latent distrust of the US.